Hofstra Professor Discusses Research On “Blackness In Malaysia”

An Anthropologist On Anti-black Racism In Malaysia

By Eric MunsonOct. 21 2022, Updated 11:49 a.m. ET

An Anthropologist On Anti-black Racism In Malaysia

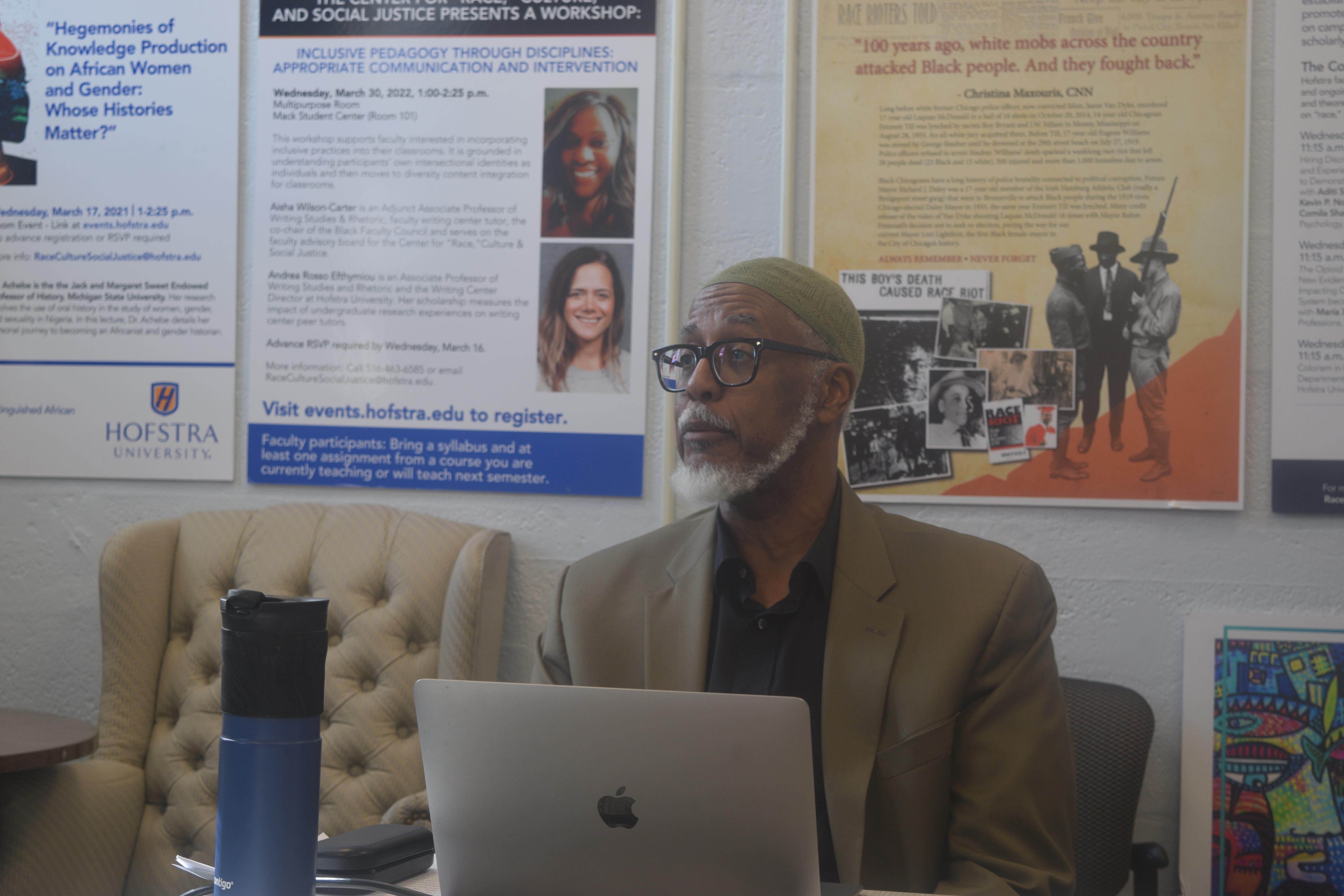

Wednesday October 19, Timothy Daniels, a professor of anthropology at Hofstra University discussed his research on “Blackness in Malaysia” at the office of Hofstra’s Center for “Race,” Culture and Social Justice in 203 Roosevelt Hall.

The event was titled “Blackness in Malaysia: Semang, Indians and Reflexivity.” It is a part of the Center for “Race” Colloquia, a series of events held on the third Wednesday of every month.

Veronica Lippencott, a professor of global studies and the associate director of the Center for “Race,” introduced the event.

“[The colloquia] is an opportunity for faculty members to present their research and publications that engage in new scholarship focusing on race and social justice,” Lippencott said.

Daniels’ research goes as far back as the 1990s, but the lecture focused on his most recent research that he did earlier this summer. He said the paper is still “a work in progress.”

“Indigenous Semang, Indians and dark-skinned visitors from Africa and North America experience anti-Black racism in Malaysia,” Daniels said. “There’s various scholarly attempts to explain contemporary racism and they often stress post-colonial radicalization and otherness stemming from Malay supremacy.”

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia with about 30 million people, the majority of whom are ethnically Malay. Chinese and Indians are the second- and third-largest groups, respectively.

Daniels visited Baling, a district in the Kedah State of Malaysia, close to the border with Thailand. Baling is home to the Indingenous Kensiu Semang, a subgroup that the Malaysian government classifies as “Negritos” or “Little Negroes.”

After arriving, Daniels rented some rooms from a Malay school teacher in the area.

“I rented two rooms for myself and my driver and then we went into the town to have dinner and we noticed that all those businesses were owned by Malays and Chinese,” Daniels said.

Daniels interviewed the Kensiu locals and learned that many Kensiu women work as either domestic servants or operators in factories. He also learned from the local leader that “there are no Semang businesses.”

“The political officials in the area have control,” Daniels said. “If you want business, you must pay fees to the government. Kensiu are not brave when it comes to business, they don’t want to compete with outsiders.”

Daniels then discussed the concept of “Orang Asli,” a Malay term translating roughly as “first people” or “original people.” Orang Asli comprise less than 1% of Malaysia’s population, but consists of numerous subgroups including the Kensiu. The “Proto-Malays” from this group are considered the closest to the Malays and “less backwards” than the Kensiu.

Daniels said that his purpose for traveling to Baling was an “interest” in the way the Kensiu had been “racialized” as Blacks in both colonial and post-colonial Malaysia.

“In many of my discussions with Kensiu Semang, not once did they refer to themselves as Black people,” Daniels said. “I never directly led them in a discussion of Blackness. I gave them chances to express a sense of their identity [and] they consistently told me they identify as Indigenous Kensiu Semang.”

According to Daniels, the Kensiu became Muslim sometime in the late 1960s. However, many of them still maintain their agency by identifying as “nominally Muslim.” Some even mix Islam with traditional Kensiu animism.

By the 1970s, nearly the entire village of about 350 people converted to Islam. Only 11 remained non-Muslim. However, this mass conversion did not make their lives much easier.

“It began with one Kensiu man who married a Malay woman,” Daniels said. “This was the first Kensiu to become Muslim. They lived in a Malay village at first, but Malays could not accept them so they moved to a Kensiu village… Kensiu could accept them even though they were Muslims.”

Daniels also visited a kindergarten where he spoke to three Malay teachers. Originally, the Kensiu and Malay students were segregated, but they decided it was better to have the Kensiu students get immersed in Malay culture.

“The teachers also told me that they feel that the children are sort of restless, immobile… they want to be independent and move around,” Daniels said. “I didn’t really see that in my observations. I really felt that the teachers were concerned and working hard, but they were still expressing some of these stereotypes.”

Daniels said that the highest level of education that a Kensiu has attained is a high school diploma. None of them have been able to get into college.

Daniels also learned about racism against Malaysian Indians during his research.

First, he attended an event in Malacca where the husband of an organization president said he disqualified a “dark-skinned Indian boy” from a Christmas party contest because “he looked like a crook.” A “light-skinned Chinese boy” won the event.

Later on, he had a seemingly civil conversation with a cake shop owner who contrasted Chinese with Indians. The shopkeeper proceeded to describe the differences between the various Indian ethnic groups.

“The Tamils were brought here as laborers on the tea and rubber estates, but the Gujarati were wealthy traders and the Bengali were guards and police for the British because they were large and trustworthy,” Daniels said, quoting the shopkeeper. “But the Tamils are not trustworthy. We say that if you see a snake and a Tamil, you better shoot the Tamil first.”

The shopkeeper laughed at his blatantly racist joke and then went back behind the counter to finish counting his inventory, according to Daniels.

Daniels then talked about “rental racism.” An African international student told Daniels that when she and her friends were searching for room rentals, the Chinese landlords told them “they don’t want to rent to any Black people, Africans or Indians.”

A Chinese-Indian man was also rejected from renting a room when the landlord found out about his mixed heritage.

Daniels ended his presentation by talking about his experiences as a Black American doing research in Malaysia.

“Malays and Chinese would often gawk at me in public,” Daniels said. “Like my experiences in Indonesia, Malaysians of all ethnicities had difficulty conceiving of a Black American… their default images of Americans are White. On several occasions I was tagged with the label ‘Negro.’”

Daniels concluded that Malaysia is more ethnically diverse than just Asians, but that much of the “white supremacy” is part of the legacy of colonialism and post-colonialism.