Hofstra University Hosts Bilingual Lecture On Quechua Language

Quechua scholar Odi Gonzales discusses relationship between language and thought

By Eric MunsonOct. 12 2022, Published 4:10 p.m. ET

Quechua scholar Odi Gonzales discusses relationship between language and thought

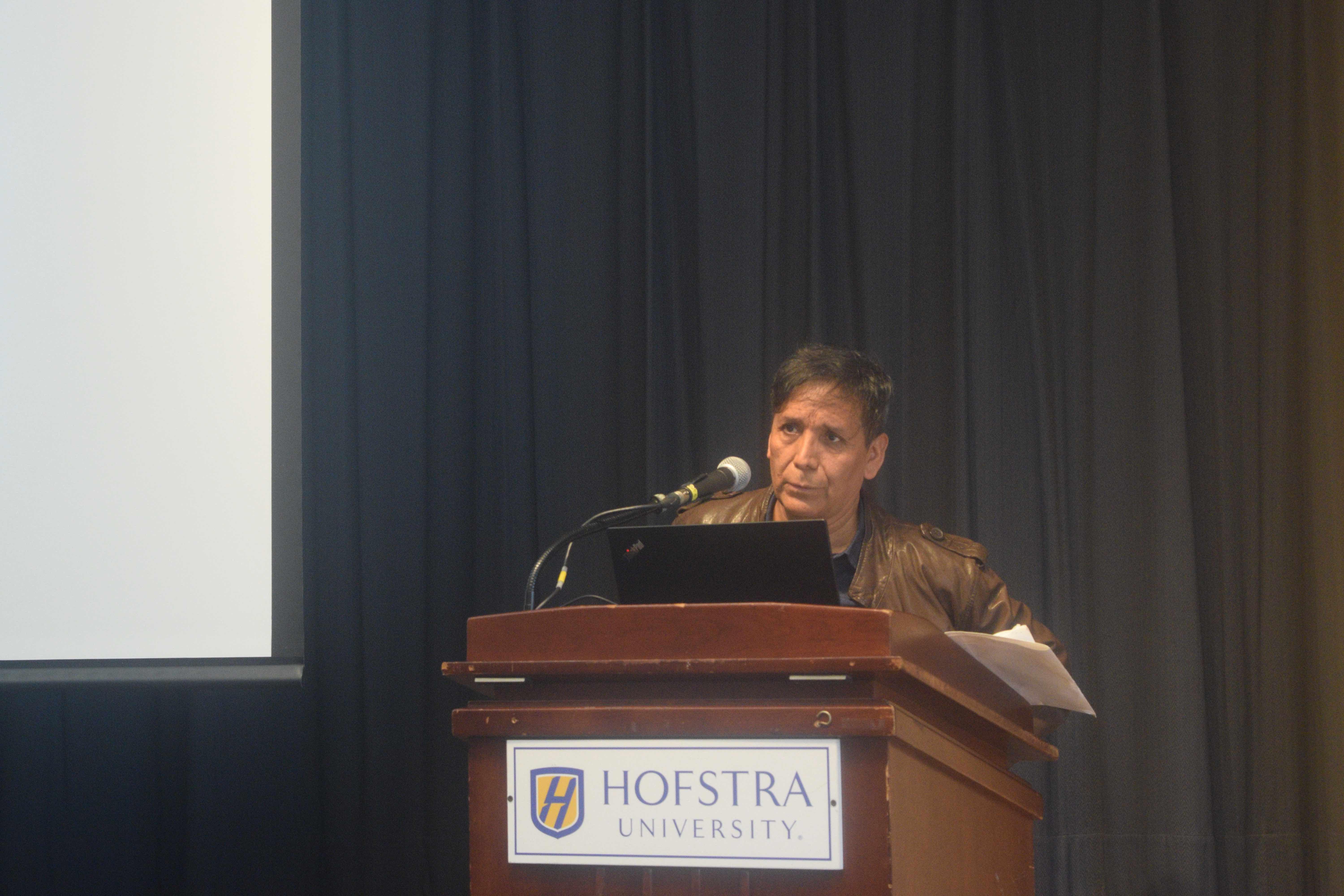

Tuesday, October 11, Hofstra University held a two-part bilingual lecture about the Quechua language, delivered in both Spanish and English, at the Guthart Cultural Center.

The featured speaker was Odi Gonzales, a poet, translator and professor of Spanish and Quechua at New York University. He spoke about how the Quechua language relates to linguistics, philosophy and anthropology, among other topics.

The first part of the lecture, which was in Spanish, focused on specific aspects of the Quechua language. The second part, which was in English, focused on the relationship between the language and thought.

“One of the most important characteristics of the language is that we not only teach the grammatical and morphological aspects, we teach cultural categories,” Gonzales said. “In Quechua language philosophy is expressed through suffixes. The philosophy is in the language itself.”

The Quechua language is an indingenous language spoken by around 10 million people in the Andes Mountains of South America, particularly in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador.

Gonzales explained that the term “Quechua” is actually a “historical mistake.” The language is called Runasimi or “language of [the] people” by the native speakers. The term “Quechua” originated from the name of a geographic region that translates as “temperate valley.”

Recently, a Peruvian writer translated “Don Quixote,” the famous novel by Miguel de Cervantes, into Quechua. However, the project took a lot of work because many concepts were difficult to accurately translate.

Gonzales stressed that traditionally Quechua was an oral language and many abstractions that would be perfectly fine in English or Spanish, would not be possible in Quechua. Gonzales said it was “shaped from a human being perspective.”

“Quechua doesn’t work with a concept of rhetorical expression,” Gonzales explained. “For example, Quechua doesn’t have ‘Thank you’ or ‘I’m sorry,’ that kind of rhetorical expression. Quechua doesn’t have the verb ‘to like’ because there’s zero action.”

Gonzales and some of his students created a trilingual dictionary in Quechua, Spanish and English. The publishers frequently complained about the way certain phrases had to be translated. Gonzales explained that Quechua is a very “precise” language.

This “preciseness” creates a simplistic grammar structure, but limits what thoughts can be expressed. As a result, it is difficult for non-Quechua speakers to comprehend.

Gonzales explained that Quechua is an “agglutinative language,” meaning that words share a common root, but the suffixes change the meaning. For example, “warmi” translates as woman, but “warmikuna” translates as women. This style can create long words that could be translated as a single sentence.

Gonzales also explained that the Quechua language does not have synonyms.

Gonzales used the example of “chewing a coca leaf” to illustrate how one simple phrase has four different words in Quechua. One word refers to the act of chewing, one refers to a ritual purpose, one refers to the medicinal use and one refers to the sound of chewing.

“The oral language is concise… a precise language to express a specific word or whatever action that we are referring,” Gonzales said. “So, the Quechua language doesn’t have interchangeable words. They have a specific word for every action. That is why I consider Quechua doesn’t have synonyms.”

Gonzales then touched on other anomalies such as how the vocabulary and suffixes change depending on whether the subject is a human, animal or an inanimate object. Some objects such as mountains and rivers, are believed to have spirits so they follow the grammatical rules as if they were human.

Gonzales described the difference between animals and humans as “instinct versus consciousness.” Humans and animals do not have the same concept of “free will.” Few other languages differentiate between humans and animals in this manner.

The Quechua have a concept of “going back to the starting point” that has two different meanings depending on the context. One refers to moving from place to place, the other is death and rebirth.

“It means that cyclical notion of time,” Gonzales said. “Do you want to study the cyclical notion of cyclical time? Here, we have [it]… in the language.”

Gordon Gilbert, a poet, is a close friend of Gonzales and compared the density of the Quechua language to the “grounded” style of American poet William Carlos Williams.

“William Carlos Williams could’ve been a Quechua speaker,” Gilbert said.

Emma Cerrelli, a Hofstra student studying Spanish, attended both parts of the event. She thought the way that the belief system “infiltrates” with the language was interesting, particularly how mountains are seen as spiritual beings and death is as simple as adding a suffix to a word.

“I thought it was just really interesting to see how their belief system and morality affects what words they use to describe certain things,” Cerrelli said.