Met Gala 2025: Superfine Reclaims Black Designers as the Blueprint, Not the Footnote

Through the lens of Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, we examine how Black designers have shaped the past of fashion and continue to lead its future.

By Bleu MagazineApril 29 2025, Published 1:05 p.m. ET

This year’s Met Gala, anchored by the 2025 Costume Institute exhibition Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, presents a critical cultural intervention—one that positions Black designers not as footnotes within fashion history, but as foundational figures. More than a theme or spectacle, Superfine serves as both tribute and thesis: a nuanced, layered exploration of how Black designers, stylists, and cultural producers have shaped, challenged, and redefined the fashion landscape across centuries.

The exhibition contextualizes the enduring relationship between Black communities and fashion, highlighting style not only as an aesthetic expression but as a tool of resistance, subversion, and cultural authorship. Central to this narrative is the Black dandy—a symbol of elegance, rebellion, and defiance. But Superfine expands beyond dandyism to consider the full spectrum of Black fashion expression, from high couture to streetwear, from Harlem ateliers to Parisian maisons.

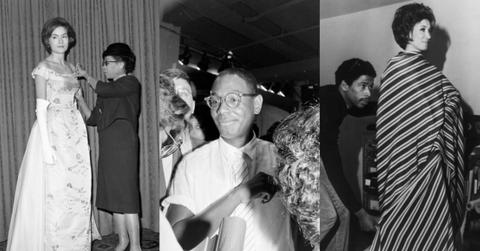

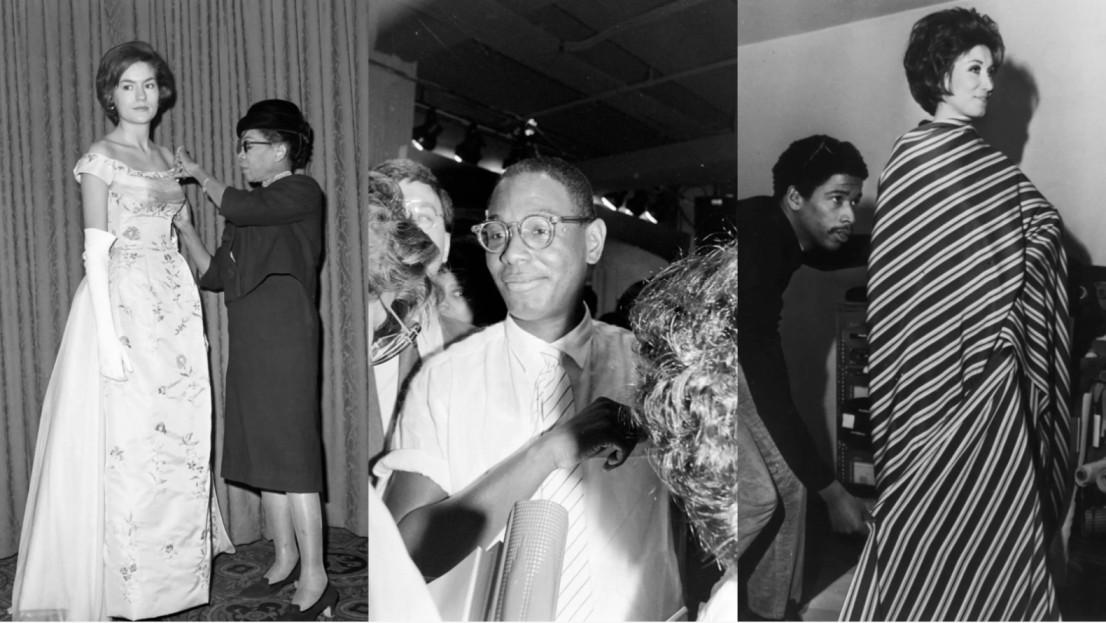

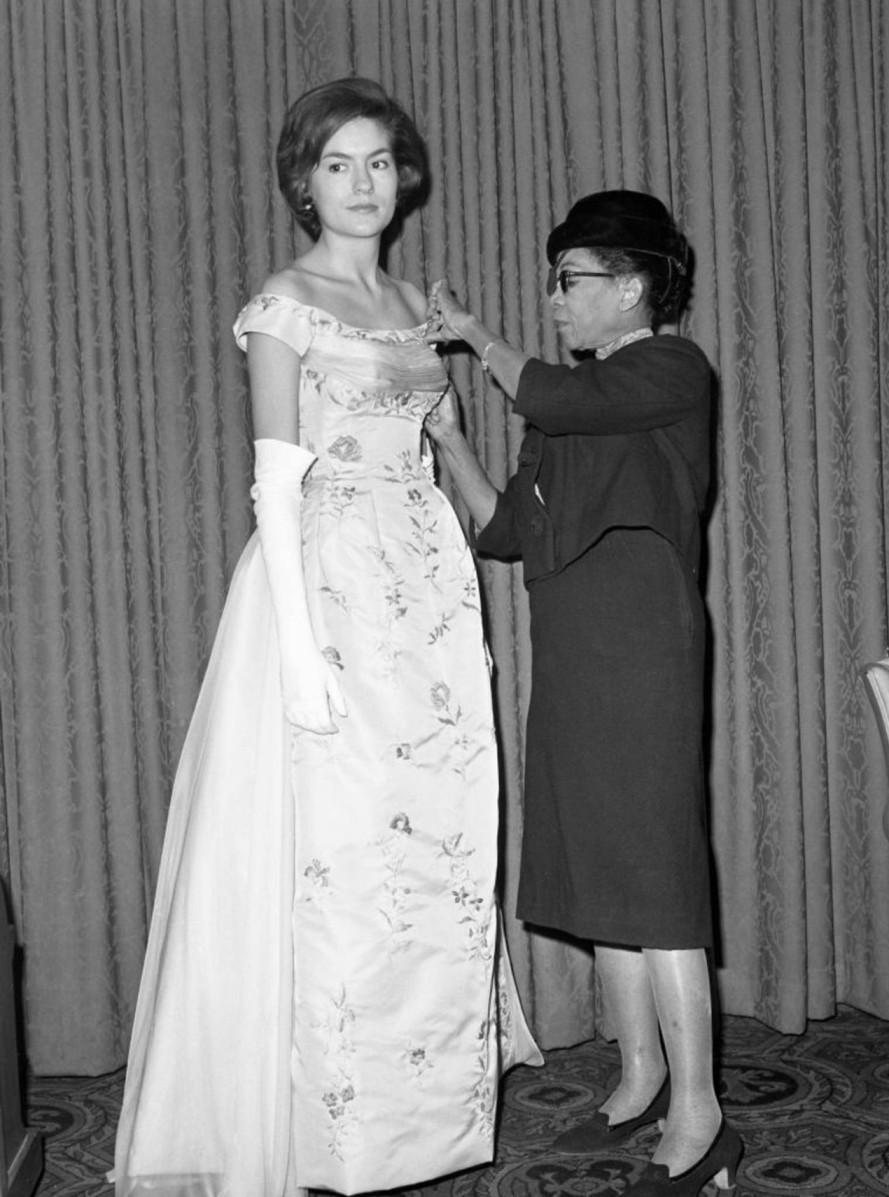

Ann Lowe adjusting the bodice of a gown she designed and worn by Alice Baker, has fitted most of the debutant and wedding dresses of the nation's top families which include Jackie Kennedy.

Throughout that legacy, Black designers have created despite adversity and exclusion. See Ann Lowe, for example, widely credited as the first prominent Black American fashion designer. Lowe, who designed Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress, was rarely acknowledged in her time; her contribution was often erased or anonymized. Likewise, Zelda Wynn Valdes, who dressed legends such as Eartha Kitt and Josephine Baker and designed the original Playboy Bunny costume, forged an early path for Black women in design. These foremothers of fashion created a framework that would later support designers like Tracy Reese, who, in the 1990s and early 2000s, led womenswear at Perry Ellis before launching her influential namesake label. Reese’s presence in the ready-to-wear space challenged the racial and gender exclusivity of American fashion’s upper echelons, which in turn laid the framework for Black femme designers like Carly Cushnie and Michelle Ochs of Cushnie et Ochs, Hanifa, Fe Noel, or London’s Tolu Coker.

Internationally, the narrative expands with figures such as Patrick Kelly—the Mississippi-born designer who broke barriers in 1980s Paris as the first American admitted to the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter. His whimsical, politically charged designs signaled a new mode of expression—equal parts joy and critique. Earlier still was Jay Jaxon, a largely forgotten pioneer who worked with the House of Jean-Louis Scherrer in the late 1960s, making him one of the first Americans— and Black designers —to helm a Parisian couture house. His path foreshadowed that of Edward Buchanan, who served as the first Black design director at Bottega Veneta in the 1990s, and Olivier Rousteing, who currently leads the house of Balmain with a vision that fuses French luxury with diasporic futurism.

Let's not forget fashion pioneers like Detroit’s Arthur McGee, who broke barriers in the 1950s and 1960s, becoming the first Black designer to run a design studio on New York City’s famed Seventh Avenue. This laid the framework for disciples like Scott Barrie and the formidable Stephen Burrows, who took the infamous Battle Of Versailles by storm in the 1970s with his flowy, fresh, bias-cut silhouettes.

The lineage continues with designers who have used fashion as a medium for cultural critique. Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss curated must-see runways that functioned as a political stage and cultural archive, interrogating the Black experience through visual language, performance art, and garment design. In 2021, Jean-Raymond made history as the first Black American to present on the couture calendar in the Chambre Syndicale’s 150-year-plus history, a milestone that also recalls Kelly and Jaxon’s paths in Paris. The late Virgil Abloh, as the artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton and founder of Off-White, disrupted the codes of European luxury by blending high fashion with streetwear, architecture, and cultural theory.

Willi Smith—often cited as the godfather of the streetwear genre, whose brand WilliWear democratized fashion in the 1980s- is an unsung figure in fashion history. Much of his approach to drawing inspiration from the streets remains the industry standard. Around that same time, in Harlem, Dapper Dan’s appropriation of European logos to create bespoke designs for hip-hop and street impresarios laid the groundwork for fashion’s current obsession with remix culture. Later, in the 2010’s, Shayne Oliver’s Hood By Air would evolve streetwear into a complex, gender-fluid, queer affirming postmodern language, while across the pond, Martine Rose was redefining menswear (and being the secret force behind Balenciaga’s menswear revamp) from London with a distinct diasporic sensibility. You can’t discuss menswear, sartorial flair, and tailoring without mentioning the impact of Ozwald Boateng, who seamlessly integrated his Ghanaian heritage into the traditional heritage of London’s historic Savile Row, and in 2003 was appointed Creative Director for Menswear at Givenchy. See, Black creation is ever cyclical.

Today's vanguard continues this trajectory. Christopher John Rogers brings maximalism and sculptural silhouettes to the forefront of fashion. LaQuan Smith designs with a contemporary understanding of sensuality and empowerment. Telfar Clemens, through his eponymous brand, reimagines luxury as accessible, democratic, and community-driven, and continues the legacy of the forever-it-bag, the shopping tote. Grace Wales Bonner merges cultural theory with British tailoring, crafting garments that are as intellectually stimulating as they are visually stunning. Sergio Hudson’s refined, power-infused tailoring draws direct lineage from both political dressing and vintage Black glamour.

Even in mass-market retail contexts, Black designers have left indelible marks. Designer Patrick Robinson’s tenure at Gap, though brief, represents a significant moment: a Black designer at the helm of a quintessential American brand. This moment reverberates in later collaborations, such as Telfar x Gap or Sergio Hudson x Target, in which Black designers brought their vision to the mainstream without compromising their aesthetic or cultural narratives.

Superfine does not merely celebrate Black designers; it attempts to center them. By doing so, this year’s Met Costume Exhibition asserts that Black creativity, dress, and style are not peripheral but central; not exceptional, but foundational. Black fashion is theory, it is archive, it is invention. It is political, poetic, and precise: Black designers have not only participated in fashion—they have defined it.

Credited to Shelton Boyd-Griffith